An Artist and Patron Conversation

A conversation between sculptor James Butler and Rod Frazer, moderated by Monique Seefried on August 27, 2017.

A transcript of the “An Artist and Patron Conversation” between sculptor James Butler and Rod Frazer, moderated by Monique Seefried, on August 27, 2017.

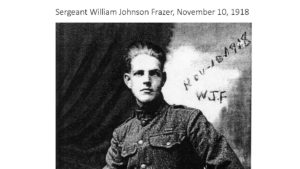

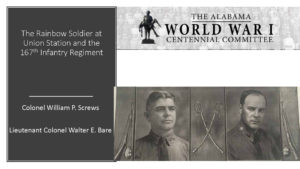

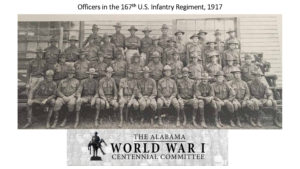

Monique Seefried: James Butler received his national diploma in Fine Art from St Martin’s Art School before spending two years in the Army as part of National Service, where he served in the Royal Signals. Following the army, he was employed as a stone carver and worked mainly in the City of London for some 10 years. In 1964, he was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts and is now its longest elected member. Since being made a member, he has exhibited there every year. His first major commission was in 1972 a twice life size portrait statue of President Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya. This led to many major portrait statues and memorials. Jim has worked continuously since on major commissions throughout the world and in England. He is equally well known for his smaller bronzes depicting dancers and nudes. James Butler lives with his wife, Angie, on an 18th century farm in Warwickshire, England.Nimrod T. Frazer is a Silver Star veteran of the Korean War, a graduate of the Harvard Business School, a successful business man and a member of the Alabama Business Hall of Fame. The son of a Purple Heart veteran of WWI, he has honored his father and his 167 th Alabama Infantry regiment by writing a book, Send the Alabamians, World War I Fighters in the Rainbow Division, published in 2014 by the University of Alabama Press. He erected a Memorial in France on the site of the battle of Croix Rouge Farm to honor all the Rainbow Division soldiers who gave their lives during WWI. In honor of his mother, he commissioned a memorial at Maxwell Air Force Base to honor the US pilots who flew in France during WWI.

Jim, you have done several very important pieces memorializing soldiers. How did you get interested in heroic art?

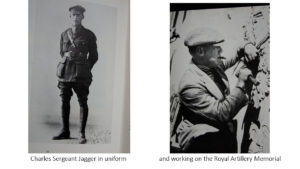

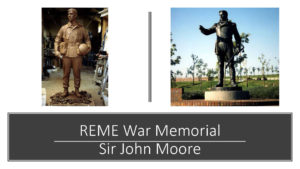

James Butler: I always have a strong affection for the work of Charles Sergeant Jagger, especially his wonderful memorial to the Royal Artillery which stands on Hyde Park corner in London. His works have always influenced me and I have been fortunate enough to be commissioned to do a series of portrait statues, the first being the figure of Field Marshall Alexander. This was unveiled by the Queen and led to a D Day Memorial to the Green Howards who lost many men on June 6, 1944. My wife and I have revisited the statue along with members of the battalion every year for over twenty years. I also was commissioned to do a figure for the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, as well as a 9 ft portrait of Sir John Moore, a member of the Green Jackets, which stands at the entrance of the new barracks in Winchester, South England, named after him.

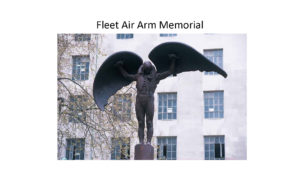

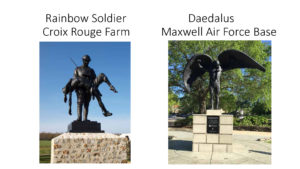

I was later commissioned by the Fleet Air Arm to make a major memorial statue to stand on the Embankment. I chose a figure of Daedalus, the mythical Greek hero, the subject of one of the great Greek fables. According to the story, he committed a crime for which he was banished on a Greek Island I suppose my interest in memorials comes mainly from my early commissions and my deep respect for the idea of a soldier giving his life for his country.

MS: Rod, after helping you locate the site of the Battle of Croix Rouge Farm in Fère-en-Tardenois where your father was wounded in WWI, I first introduced you to the great nephew of Camille Claudel, the mistress of Rodin and a great artist in her own right. The Camille Claudel Museum opened this spring in Nogent sur Seine but some of her major works have been since decades in the Musee Rodin in Paris and the Museum of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. She was born in Fère-en- Tardenois where the battle of Croix Rouge Farm took place. Calyxte, her great nephew is a well-established sculptor who does work in Europe and the Americas and his links with Camille Claudel and Fere-en- Tardenois were important. But the chemistry was not there. I then introduced you to James Butler and you did your due diligence before meeting him. What made you decide on Jim?

Rod Frazer: I didn’t want to meet Jim before having seen some of his work. I first went to Normandy to the landing beaches of WWII to see Jim’s memorial to the Green Howards in Crepon. The realistic humanity of the seated soldier is startling. You think he will start lifting his head to look at you. The work expresses so well the weariness of the soldier. I then went to London and admired Jim’s impressive statue of Field Marshall Alexander, by the Wellington Barracks across from Buckingham Palace. It was then that I realized that Jim Butler had been the sculptor responsible for the Fleet and Air Memorial on the Thames Embankment, a statue that touched me. I was ready to meet Jim, but before doing so I went to the WWI memorial that has always impressed me the most: the Royal Artillery Memorial at the corner of Hyde and St. James Park. I contemplated it for a long time, wondering how anyone could ever equate the perfection of Charles Sergeant Jagger. That was what I wanted.

Then I went to Banbury and met Jim in his studio in the country. We talked about Jagger and the Michelangelo work at the Vatican, the Pieta, Mary holding the broken body of Jesus.

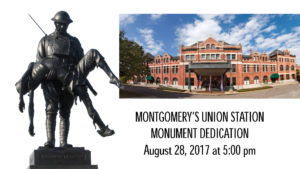

I asked if there was anything in his heart that he had always wanted to do. He removed a piece of paper from a nail on the wall with stick figures. It was the beginning of the Rainbow Soldier. He asked what I wanted. I told him that I had seen dead American soldiers and they all looked like rag dolls. That was what I wanted. The discussion went quickly to timing and business aspects of the commission. It was realized and inaugurated on the site of the second most important battle in the history of Alabama after Little Round Top in November 2011 after being exhibited in the courtyard of the Royal Academy during the 2011 Summer Exhibition.

MS: Why did you want to memorialize your father and honor the Alabamians in the Rainbow Division? What did WWI mean for Alabama?

RF: My father was dead and had not been suitably memorialized. We were never close but I knew he had an authentic record as a combat soldier. Service in the Rainbow Division was the absolute highlight of his life. I respected that as worthy of an heroic memorial in the manner of Jagger.

The National Guardsmen leaving Alabama were mostly poor young grandchildren of Confederates, very provincial and, for the most part, poorly educated. The French welcome had a profound impact on these men. For many of them, France was as foreign as life in an Afghan village must be to Alabamian soldiers now, but some had a sense of French culture. A significant portion of Alabama had been part of French Louisiana and many knew families or towns with French names and they all knew about Lafayette.

In the beginning, they were stationed in eastern France, a relatively quiet area. They were greeted in villages with only women, dressed in black, old men and children eager for the presence of these Americans who played games with the kids, helped the women with farm work and brought laughter in place which had only seen gloom for the past 4 years. After entering into combat, they were lionized by the French for their courage in front of the enemy. After 18 months in Europe, they returned home not only as full Americans having fought side by side with the descendants of Union soldiers but as citizens of the world.

And they returned to a different country, a difficult return for many of them. It is not the place to speak here about the impact of WWI on our country but it was huge. The United States was transformed more than at any other time in its history. This statue of the Rainbow Soldier should be an icon in Montgomery between the old and the new South, even if many traditions of the Old South had not yet been abolished. But it should symbolize the entrance in a new era, just as I hope the QR code on the plaque of this statue will symbolize the 21st century we have now entered.

MS: what attracted you in the project of the Rainbow Soldier? Would you mind sharing with us your creative process?

JB: It was the chance to make a large statue of one of the most heroic deed one can think of, the rescue of a soldier from the battlefield. I am not personally a religious person but this whole project had a very powerful spiritual effect on me. There were periods in the modelling of the figure when the form was being made by a stronger and more powerful creative force than my own. I almost watched my hands model part of the figure of the soldier. It may sound rather fanciful at this moment but at the time, when I was alone in my studio, I did feel that my hands were somehow guided.

This remains for me to be my most powerful and spiritual work.

MS: could you compare the creation of the Rainbow Soldier with the Daedalus?

JB: The Daedalus came first in the commissioning of my statues and of course, this is a mythical figure, the myth being that Daedalus was wonderfully gifted engineer, architect, artist, absolutely anything he could do and he was fiercely of his own image and in a fight with a colleague, he committed a murder and was banished with his son Icarus to a Greek Island. But of course Daedalus was a man of many parts and was able to make wings from local materials that would allow him and his son Icarus to fly away. Icarus of course was a young teenager and as most teenagers nowadays didn’t obey his father command not to fly near the sun. He did so and the sun melted the wax used to tie his wings together and unfortunately he plunged into the sea. Daedalus however escape and became the symbol used by the Fleet Air Arm. The Soldier in my mind was not a myth but felt like a real thing and therefore I had to be more conscious of the reality of what a person looks like than with the freedom I had creating the idea of Daedalus.

Therefore the figure of Daedalus is a powerful image, the wings that he made have great handles and they are hinged at the back so his use of the wings would have some symbol of reality. He is clothed with an overall that covers his lower body and leave his arms and legs uncovered so that we can see the strength he must have used in order to affect his escape. Although the idea of Daedalus is basically a fairy story, Daedalus in my mind is also a real person and I modelled him as such,

He is looking down at us and his head is skull like and they are deep hollows for the eyes.

MS: As soon as you saw the Daedalus mold in Jim’s farmhouse, you thought about Maxwell, tell us why and also what it meant to you to memorialize your parents individually through those extraordinary works of art?

RF: My parents were divorced when I was quite young. My mother was strong with a life of her own. She deserved a unique memorial, something that was as uplifting as she was to me. My brother and I had previously memorialized her by publishing her work on genealogy and our family since the American Revolution. I then figured it was time to do something for the old man and I went back on his footsteps in France, saw the battlefield he has been wounded, and decided to honor him there with his fellow comrades of the Rainbow Division. Years later, after Jim’s success with the Rainbow Soldier I commissioned him to do a casting of the Daedalus in honor of my mother, a humble civilian employee at Maxwell. I gave the sculpture to the United States Air Force. It is magnificent and is displayed at Maxwell in a park in front of the Maxwell Club, a perfect place.